Discover the quirky sides of Iowa’s history through these 13 intriguing artifacts, which expand on already-known stories surrounding WWI, railroads, wildlife past and present, Victorian life and more.

Sweet Vale of Avoca Museum - Avoca

Donated by a local beautician when she retired, the medieval-looking permanent wave machine device maintains its reputation as a conversation piece at the Sweet Vale of Avoca Museum. The machines were most popular during the 1920s and 30s when beauty parlors first entered the beauty industry. While these shops created places for women to gather and socialize, they also kickstarted beauty culture. Using an electric current to heat the hair that was clamped in sections on rods, it could curl the straightest hair and straighten the curliest hair. However, since it used temperatures of up to 200 degrees, the process left the hair stiff and brittle and ran the risk of burning the customer and beautician.

University of Northern Iowa’s Rod Library - Cedar Falls

Hidden among the bookshelves and studious students that fill the University of Northern Iowa's Rod Library lies an interesting piece of Iowa history. Inside a glass display case lies an ancient mastodon tusk discovered on a farm near Hampton in 1933 after the farmer noticed a horn-like object sticking out of his gravel pit. At the time of its discovery, it was the largest intact tusk found, measuring over 11.5-feet long and over two inches in circumference. Eventually, the tusk was brought to the Cedar Falls university for conservation and exhibition and, in 2017, it underwent a massive conservation project. The project was conducted alongside the Department of Chemistry’s Instrumental Analysis class on campus, whose research helped determine what was previously done and what can be done in the future to preserve the tusk. Their work, along with additional research pertaining to mastodons and the Pleistocene era are on display next to the tusk, which can be viewed year-round during library hours.

Brucemore - Cedar Rapids

Though the Brucemore Mansion is an impressive structure itself, it hides a miniature room within its walls. The tiny tavern was developed by miniature room artist J.H. Hoffheimer to depict an 1890s-style bar room. It was gifted to Howard Hall, the mansion’s final resident, in March 1950 by a friend. Referring to it as “Duffy’s Tavern,” Howard said, “It is really one of the cleverest things I have ever seen, and would rather have it than a nice painting, which probably shows my low-brow rating. Possibly some of my great-grandfathers were horse thieves or bartenders.” The 1890s were a nostalgic period for Americans in the early and mid-twentieth century. Though the decade was marked by economic turmoil, it was also idealized as a time of pre-income tax wealth and fascination with high-society lifestyle. Nostalgia for the bars of that era also grew during and after the repeal of prohibition.

Union Pacific Railroad Museum - Council Bluffs

Created with a similar idea to the well-known handcuffs, thumbcuffs easily fit into railroad special agents’ pockets, allowing them to be successfully undercover. This clever device was invented by a Seattle police office in the late 1920s, but proved to be unreliable and dangerous as the cuffed individual could tear their thumbs off in an attempt to escape. The thumbcuffs and other unique items are featured in the Union Pacific Railroad Museum's Law & Order on the Railroad exhibit, which is on display through Council Bluffs’ Railroad Days event in September.

German American Heritage Center - Davenport

Visit the German American Heritage Center to take a close look at the pair of German immigrant shoes worn by 12-year-old Minnie Boister as her family made the trek across the Atlantic Ocean. Born in Germany in 1875, her family immigrated to the U.S. in 1887 and settled in Illinois before she moved to Wheatland, Iowa, as an adult. The journey was no easy feat as conditions on the ships in the 1880s were horrifying. Passengers were often cramped in close quarters with strangers, beds were sometimes infested with lice or other insects, and illnesses like sea sickness overcame many. As each family could carry few possessions, passengers were also stuck wearing damp clothes or sleeping in damp bedding for weeks at a time if they could not access their trunks. The shoes are part of the Davenport museum’s permanent exhibition, The German Immigrant Experience, and were worn by Minnie from the moment she left her home in Germany to the time she stepped on American soil. They are made from hand-formed wood and leather attached with wire and staples.

Putnam Museum - Davenport

While strolling through the Putnam Museum’s Black Earth/Big River exhibit in Davenport, you may have to do a double take when you spot the albino raccoon. Hidden among the limbs of a giant oak tree, the rare raccoon is the result of a genetic mutation that creates the “blonde” or white fur as well as pink skin and pink or light blue eyes. Due to this light coloration, their lives can be challenging as they are easy targets for predators and battle strange conditions like sunburns.

Des Moines Art Center - Des Moines

Bruce Nauman took inspiration from the Des Moines Art Center’s Richard Meier wing, whose geographical shapes reminded him of a pyramid, and the nearby Greenwood Park to create Animal Pyramid. Made specifically for its outdoor location at the Des Moines museum, the unique sculpture maintains the artist’s reputation for creating images of animals engaging in unnatural activities. Its permanently located on the north lawn, offering an absurd image that’s seen as darkly humorous and has several interpretations. Some perceive it as a strange circus act while others see a bizarre taxidermy display. A deeper interpretation views the animal forms as stand-ins for humanity and the pressures society and culture place on us to perform or act in certain ways.

Hoyt Sherman - Des Moines

While strolling through the stunning Hoyt Sherman mansion in Des Moines, visitors often stop to admire a strange-looking wreath in Helen Sherman’s bedroom. They are shocked when they learn what it’s made of – human hair. Well, hair, wire, ribbon and wood, to be exact. Crafted by Ida Beighley Hilty, this Victorian hair wreath was created to mourn the loss of a loved one and was passed down through her family until the Shermans acquired it. They were a common grieving practice during the Victorian Era. The hair often came from the person who had passed away, collected from brushes and combs then stored in a special container called a hair receiver. Then, the strands were wrapped around a support, usually wire, and fashioned into fanciful designs, but left open-ended in a horseshoe shape to catch good luck.

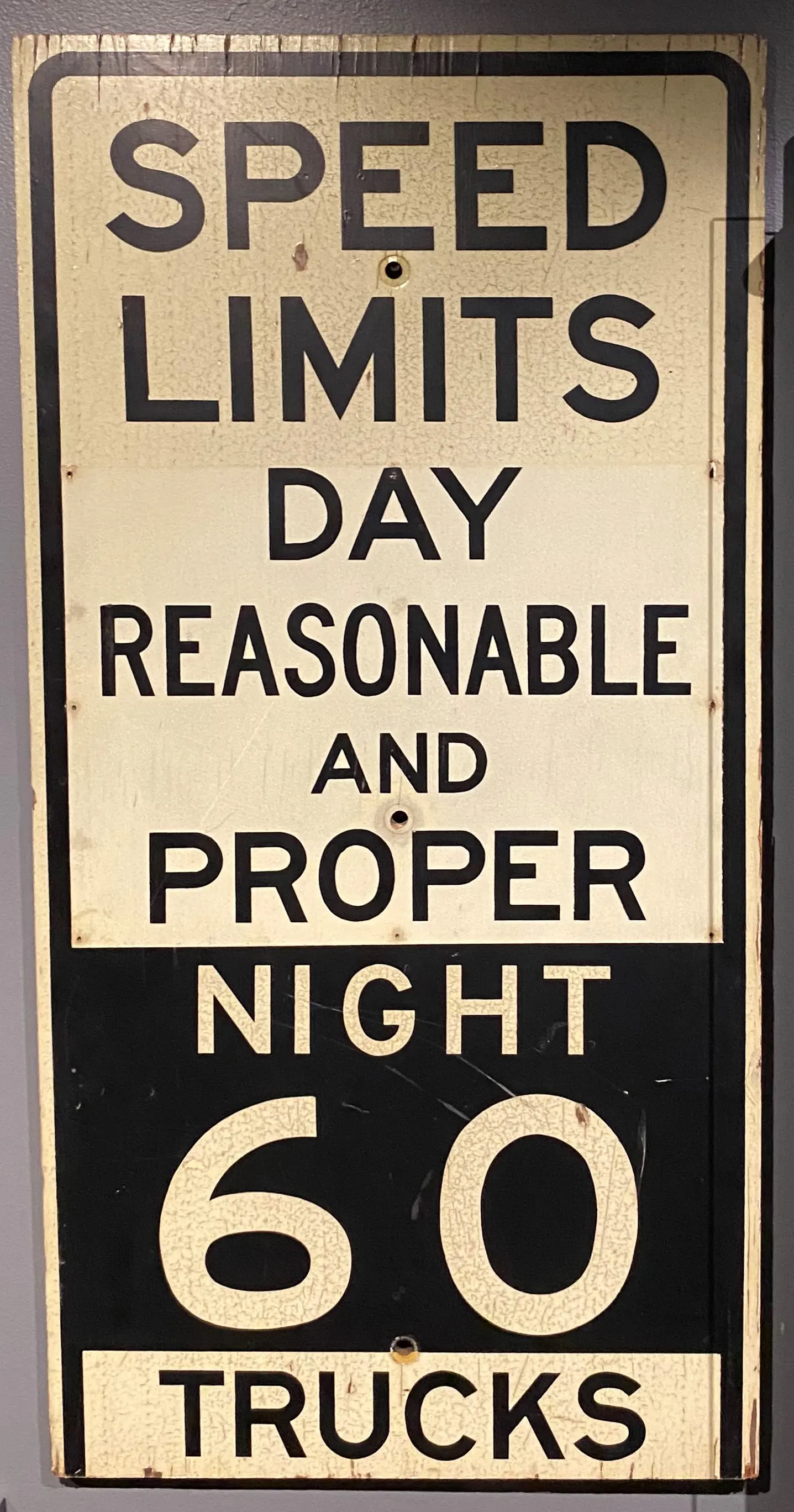

State Historical Museum of Iowa - Des Moines

Located in the State Historical Museum’s “Visible Vault,” this peculiar road sign speaks to the old-time balance between regulation and liberty. Dated around 1958, it reflects a time when there was no speed limit on two-lane highways during the day, and drivers could travel at whatever speed they wished if they maintained control of the vehicle. But, once the sun set, drivers had to abide by a 60-mile-per-hour speed limit. This Iowa speed law held until 1959, after which a 60-mile-per-hour limit day and night was put into practice. Then, in 1974, the federal government began enforcing the 55 mile-per-hour speed limit that many states still enforce today.

Shelby County Historical Museum - Harlan

At the Shelby County Historical Museum in Harlan, a plain-looking box surprises visitor after visitor. Dating back to WWI, the shoe-fitting fluoroscope was invented by the U.S. military during an intense study of the fit of boots and the effect on soldiers’ health. It worked by placing your feet on the ledge and through the opening, then looking down through the viewing porthole at the top at the x-ray view of the feet and shoes. Two other viewing portholes on either side allowed others to observe the same view. After the war, this contraption was commonly found in podiatrist’s offices and shoe stores, though articles relating to their use seldom claimed that they improved a shoe’s fit. Shoe salesmen instead used them to persuade customers to buy more expensive shoes.

Stanley Museum of Art - Iowa City

Crafted from wood, human hair, glass beads, cowrie shell, pigment and cloth, the Bamiléké-Dogon Ku’ngang African mask is part of the Stanley Museum of Art's Visages de Masques (Faces of Masks) exhibit. The artist, Hervé Youmbi, creates such pieces to question the impact of colonization and its effect on the production of masks that are still used for worship and rituals in Africa. This project is especially unique because it reverses the historical trajectory of such masks that typically appear in displays in Western museums – it’s only on exhibit in Iowa City when the artist isn’t using it in sacred performances in Western Cameroon. Each time it returns to the museum in Iowa City, the mask’s appearance is slightly altered due to use, allowing visitors to appreciate it anew with each visit. The display also includes a video of the mask being worn during such performances, providing an opportunity to admire it in action.

McCallum Museum - Sibley

While exploring the diverse mix of the McCallum Museum's exhibits that include everything from horse buggies to WWI artifacts, visitors are often surprised to wander across a display case that contains a two-headed calf. Said to be the Sibley museum’s claim to fame, the calf’s intriguing story dates to 1936 when it was born on Emil Braun’s farm just north of town. The calf did not survive long after its birth.

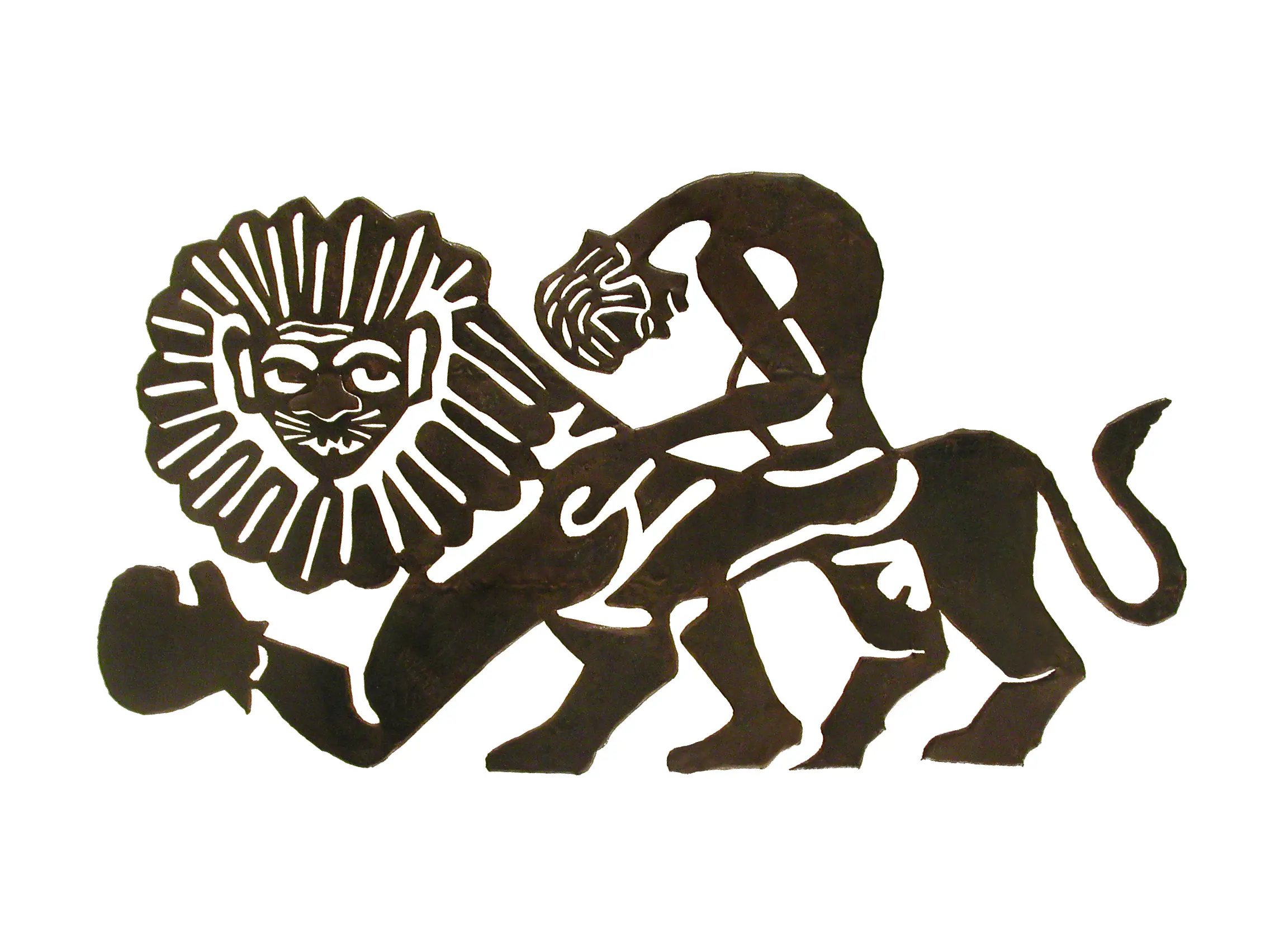

Waterloo Center for the Arts - Waterloo

Murat Brierre’s metal cutwork piece titled "I fight like a lion" stands out to Waterloo Center for the Arts visitors and museum curators alike. Measuring 60” across and 30” wide, this piece fills a wall in the Reuling-Feldman Gallery, which is permanently devoted to artwork from Haiti. (Fun fact: the Waterloo art center is home to the world’s largest public collection of Haitian Art.) This technique is called fè koupé, which translates to cut iron as Haitian artists often flattened and repurposed discarded oil barrels to use as a canvas for carefully planned designs. When admiring this unique work, the museum encourages visitors to consider themes and interpretations related to spiritual metamorphosis and a reverence for the heroic legacies of strength.